Today is Decker’s third birthday, and that means we’re well due for another periodic summary of progress, reviewing changes between version 1.44 and 1.60:

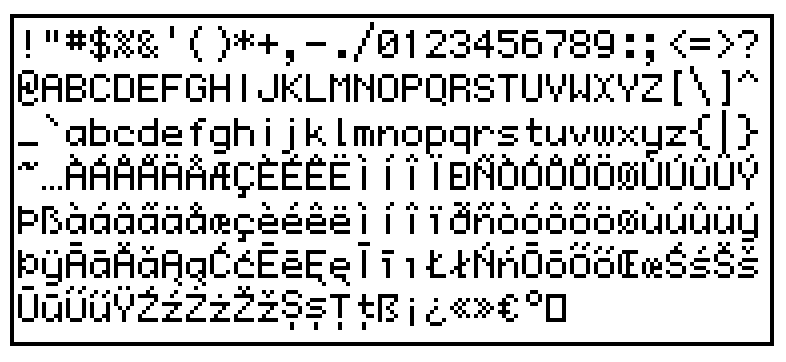

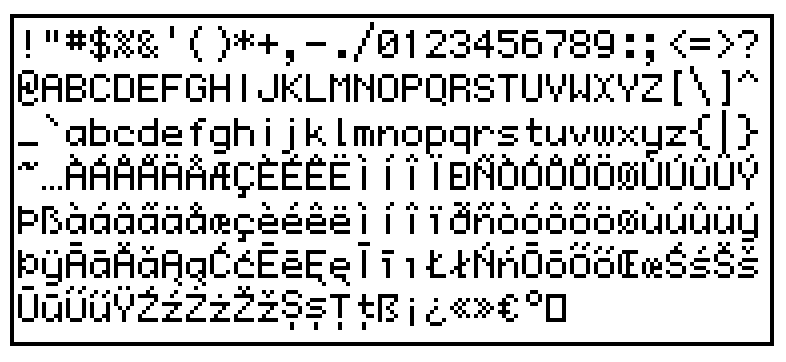

By far the most impactful change this year was the introduction of DeckRoman, a carefully-selected subset of Unicode which allows Decker to represent and display text from a wide range of non-English languages, including French, Spanish, German, Polish, Portuguese, Hungarian, and Romanian. Decker ships with a variety of bitmapped fonts which support the complete DeckRoman character set as well as a new and improved Font Editor Deck with tools that make it easy to add the new diacritics and special characters.

By popular demand, Decker has also gradually expanded support for color (which includes animated patterns, for fans of the <blink> tag):

_fg and _bg.t or T format code.

Importing images now respects the “Color” setting in the “Style” menu, either applying a 1-bit Atkinson Dither or posterizing color images to Decker’s 16-color palette. Want to customize the palette without using any extra contraptions or writing code? Just drag and drop one of the .hex files you can find on LoSpec.com onto the Decker window! Decker’s “animated patterns” have also been expanded to allow sequences up to 256 steps long, permitting slower, subtler, and more intermittent patterns than the previous limit of 8 steps. If you’d like to know more about how Decker handles color, check out the new interactive guide All About Color.

Another common request for Web-Decker in particular is direct access to JavaScript and browser APIs. While Decker sandboxes decks for many good reasons- including portability and user privacy- the danger zone offers an officially supported opt-in mechanism for seamlessly interoperating between Lil and JavaScript:

danger.js["2+3"]

# 5

danger.js["x=>3*x" 7]

# 21

danger.js["f=>f(f(47))" (on twice x do x,x end)]

# (47,47,47,47)

The Forbidden Library offers a selection of premade Lil modules exclusively for Web-Decker that wrap commonly requested functionality, like the ability to perform HTTP requests. Use if you dare!

In a dense UI, overlapping widgets can become very cumbersome to select and reorder. To solve this problem, Decker now features a dialog box that shows every widget on a card by name, and permits reordering and selection within this list view:

](unionstate3-figures/widgetsorder.gif)

Setting up rich-text “links” to other cards in a deck was potentially error-prone, since it had to be done “blind”, assuming user knowledge of the destination card’s name. There’s now a visual picker available, similar to the dialog used for setting up Button Actions:

When creating animated “sprites” that need to stand out visually against complex backgrounds (especially in 1-bit graphics), it’s often useful to give them a contrasting outline. The new “Add Outline” feature in the “Edit” menu makes this fast and easy. Note that image.outline[pattern] is also available at a scripting level:

The name of a card or prototype, displayed in the top right corner of the menu while editing, is now clickable, serving as a shortcut to the corresponding properties dialog.

Web-Decker has long had support for “deep-linking” by supplying a card name as a URL hash; to make this feature even more prominent and easier to use, Web-Decker now automatically updates the hash as you navigate through a deck. If a deck is hosted online, it is thus just as easy to link another user to a card as it is to link them to any other webpage.

Decker avoids exposing direct access to low-level keyboard events for the sake of portability. Decks are intended to be usable on touch- or pen-based devices that don’t necessarily have a physical keyboard. Using Decker’s onscreen “soft keyboard” to edit the contents of a field is transparent to scripts; they can’t change the contents of a field while it remains selected. There is one exception to this rule: it is now possible to clear a selected field, dismissing the soft keyboard and defocusing the field while in touch mode. This tweak makes it possible to build REPL-like user interfaces within decks without sacrificing touch compatibility. Harlequin Diver’s work-in-progress The Dreams In The Peacock House illustrates using this feature to blend parser-based interactive fiction with elements of visual novel presentation and point-and-click adventure games. I also built a simple IF Parser Demo that illustrates how Decker’s ordinary widgets-and-events model can be used to simulate rooms, objects, and verb dispatch within interactive fiction:

A very subtle improvement to Web-Decker’s generality is support for very small decks: previously Decker restricted deck size to a minimum of 320x240 pixels, but they can now be as small as 8x8 pixels. It is also possible to use the new deck.corners property to hide or recolor the rounded corners Web-Decker normally applies to Decker’s display. Together, these changes make it more feasible to blend decks within <iframe>s seamlessly into websites, introducing the same kinds of decorative interactivity that once was the domain of Flash. Authoring custom-sized decks presently still requires some manual editing of .deck files; there’s ample room for improvement if this use-case is popular.

There were also a wide variety of smaller additions and expansions to Decker’s scripting APIs. To summarize briefly:

image.pixels permits bulk reading and writing of every pixel in an Image Interface, allowing Lil to bring its vector-oriented primitives to bear on image manipulation.image.scale[x 1] allows an image to be scaled to a specified size x rather than by a scaling factor x, simplifying the flow of many image preparation “pipeline” expressions.image.merge[] can now use the * operator when merging pixels of two images, for better generality.image.bounds efficiently computes a bounding rectangle for the opaque pixels of an image.field.images extracts a list of all the inline images from a rich-text field, simplifying storage and retrieval of bulk graphics: flipbook frames, game sprites, icons, etc.field.scrollto[char] and grid.scrollto[row] provide a more convenient way of scrolling to reveal a position in the content of the widgets, rather than a specific physical scrollbar position. Fields are further aided by the addition of rtext.index[table (line,col)] and rtext.find[table key ignorecase] for locating meaningful character positions within rich-text._hideby: when present, rows are visually suppressed anywhere this column contains a truthy value. This makes it possible to search and filter the rows of a grid without physically removing them from the underlying table, and thus avoids the need to separate a “display” grid from a “backing store” for simple databases.eval[] now offers an errorpos key in its result dictionary specifying a line and column position within the evaluated source code, making it easier for tools built upon it to report syntax errors usefully.random[] called with no arguments now produces a floating-point value between 0 and 1.import[] can now directly import a .deck file, obtaining the modules stored within it, further cementing decks as a first-class way of representing reusable resources, even for command-line scripts.deck.remove[patterns] offers a convenient way to reset Decker’s 1-bit patterns, animated patterns, and color palette to their defaults.write[image palette] allows Decker to save GIF images (possibly animated) with an arbitrary palette of up to 256 24-bit colors.read["deck"] and write[deck] can now read and serialize decks, making it possible to use Decker to build tools for manipulating other decks, like tools for fusing multiple decks together, localizing the text in a deck, or converting games made in other engines into decks. These generalizations also introduce deck.encoded as a way to stash a deck temporarily as a string and newdeck[] for creating a new Deck interface from such a string or entirely from scratch.app.render[card] or app.render[widget] can be used to take a “screenshot” Image of cards or widgets, making it easier to generate documentation or illustrative GIFs from within Decker..parent attribute, making it easier to navigate the container hierarchy directly.Additionally, Decker now comes with a variety of new and expanded modules and tutorial decks:

!flip, !shake, and !play.Melt and ClockIn.This year’s changes to Lil have mostly been more subtle than the previous year, reflecting a slow “cooling down” of the design, but there were nevertheless a few impactful surprises:

The new window operator mirrors a similar primitive in K: with a positive left argument, it slices a list into equal-sized non-overlapping runs (bucketing), whereas a negative left argument produces overlapped windows:

3 window "ABCDEFGHI"

# ("ABC","DEF","GHI")

-3 window "ABCDEFGHI"

# ("ABC","BCD","CDE","DEF","EFG","FGH","GHI")

As a practical example, consider the following two methods for bucketing the cards of a deck into pairs for a print layout:

extract list value by floor index/2 from range deck.cards

2 window range deck.cards

Several built-in functions like print[] and bits.xor[] can take any number of arguments. Lil can now define functions which accept the same convention and receive their arguments as a list:

on vary ...x do

print["called with %i args: %J" count x x]

end

vary[] # called with 0 args: []

vary[11 22] # called with 2 args: [11,22]

Lil has always been able to work with JSON data, but several of Lil’s datatypes can’t round-trip in that format without extra work. This year, I introduced a JSON superset called LOVE which solves this problem, providing serialization of tables, non-string-keyed dictionaries, images, sounds, and byte arrays. Lil offers the %J symbol for parsing or formatting LOVE data (as opposed to %j for JSON), and in Decker you can use the new .data attribute of field widgets to stash any LOVE-compatible data painlessly:

# explicit encoding/decoding

f.text:"%J" format x

x:"%J" parse f.text

# implicit encoding/decoding

f.data:x

x:f.data

Guided by applications, I made performance improvements to a number of special cases in various operators: table join table, list in list, unaryprim @ x (like sum @ x), dict @ list, and list @ list are all substantially more efficient due to a mixture of more specialized bytecode generation and less naive algorithms. There’s still substantial room for improvement; a ground-up rewrite of the native Lil interpreter with some changes to the internal representation of various datatypes may be in the future.

There was also some improvement to the generality of @: it’s now possible to repeat this operator in order to “push” it down deeper into a data structure:

a:"%J" parse "[[[1,2],[3,4]],[[5,6],[7,9,10]]"

count a # 2

count @ a # (2,2)

count @ @ a # ((2,2),(2,3))

count @ @ @ a # (((1,1),(1,1)),((1,1),(1,1,1)))

The largest breaking change to Lil this year was the introduction of a nil datatype. Avoiding a first-class type for representing absence and simply treating missing values as 0 was an experiment in keeping Lil’s design as small as possible, but the lack of nil lead to a variety of odd and inconvenient coercion behaviors. Having a “plastic” nil which can coerce to context-appropriate empty values leads to fewer surprises:

# old behavior

1+undefined # 1

"%s" format undefined # "0"

# new behavior

1+undefined # 1

"%s" format undefined # ""

This also comes with the addition of the fill operator as a vector-oriented equivalent of the unless operator for coalescing nils into substitute “default” values as needed:

3 unless zilch # 3

3 fill (11,zilch,22,zilch) # (11,3,22,3)

Beyond the tool itself, the Decker user community has had a number of interesting developments and new faces over the course of the year.

One of the largest surprises this year was the explosion of enthusiasm around WigglyPaint, a drawing program I built in Decker. It automatically applies a line boil animation effect to all brushstrokes, and provides the user with a selection of limited but artistically interesting drawing tools and palettes. By keeping everything very simple and “juicy”, users often find it’s a great way to break out of artist’s block and embrace making imperfect doodles:

After nearly a year of a slow trickle of users steadily posting doodles and enjoying themselves, WigglyPaint inexplicably went viral among online artists, leading to (at time of writing) nearly 4 million browser plays on itch.io. The comments section sports thousands of wiggly doodles, and if you search for #wigglypaint on your favorite (or least-dreaded) social media website, you’re sure to find plenty of drawings and videos.

It’s fun to see one of my projects get this level of attention, but I also see it as a valuable “social proof” of Decker as a development tool: the countless millions of WigglyPaint enthusiasts aren’t enjoying it merely as a deck, but on its own merits as an application. I have been a bit disappointed by the numerous copycats which have rehosted WigglyPaint on their own websites, often visibly slop-encrusted and in many cases misrepresenting themselves as me. I won’t link to any such sites, for obvious reasons, but it’s not all gloom and plagiarism. For example, a Chinese user who goes by “Pulupo” delightfully localized WigglyPaint (and Web-Decker) and made a variety of tweaks and customizations to the painting tools:

We’ve held a number of “Game Jams” for Decker over the past year. I hosted the regularly-scheduled Dec(k)-Month in December and Decker Fantasy Camp 2025 in July. These were additionally joined by Treegravy’s Decker VN Jam, which focused on authoring visual novels, and Swanchime’s Pink Decker Jam, which was themed around a dazzling custom palette. It’s very exciting to see new users host their own events like this, and I’m hopeful we’ll see more in the future!

I’ve also observed a number of long-running serialized “Zines” released partially or entirely in Decker. Consistent forums contributor Millie has been producing issues of her Zine of Millie since late 2022, and released her 32nd issue this month. We’ve also seen regular discussion of Decker-based media and supplementary issues from Houdini Magazine. Indiepocalypse, a monthly anthology of indie games, regularly features games made with Decker:

by sweetfish](unionstate3-figures/eidercake.gif)

by Olszoj](unionstate3-figures/syf.gif)

Decker’s emphasis on reified data and spatial organization means that complex decks often have “backstage” areas that are used for storing information and resources but rarely visited outside debugging and development. Some deckbuilders leave behind fascinating notes, leftovers, and prototypes, while others go several steps further and create stunning supplementary experiences like the backstage area of Ahmwma’s Riddle of the Temple:

At time of writing, we’re up to 213 games on itch.io tagged with #decker.

Decker continues to grow more powerful and more accessible thanks to feedback, encouragement, and constant experimentation by our vibrant community. I’m proud of how far we’ve come, and excited for what the future holds.

Like what you see? Join us on the Decker community forum! We can always use more help spreading the news about Decker and getting it into the hands of new creators.