HyperCard is one of the most influential pieces of software in history, providing a rich and extensible programming environment that was truly in the spirit of the Macintosh: visual, immediate, accessible.

Today there is no shortage of tools claiming the mantle of The Modern HyperCard. Curiously, these visions of the future often have little structurally or conceptually in common with their supposed ancestor- or one another. From “low-code” web application builders to Mathematica-inspired notebook environments to note-taking applications (and- distressingly- quite a few hands-free slop-generation tools), it seems as though everyone who reaches for HyperCard grasps at a different shape. For many, “HyperCard” is perhaps more of a feeling of empowerment than any particular manifestation of features on a computer.

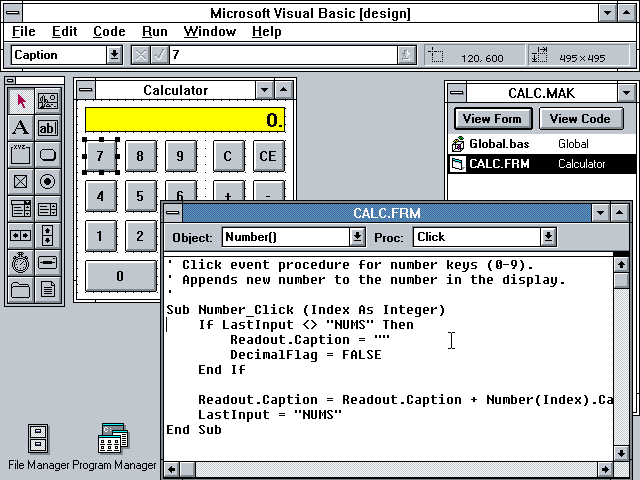

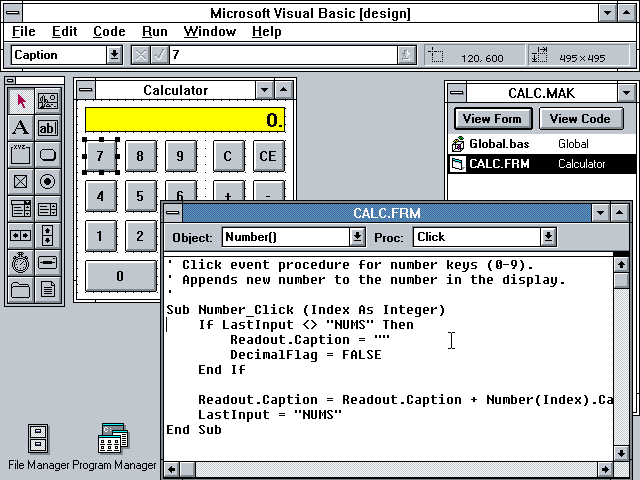

The most common flavor of “Modernized” HyperCard aspirants seems to hew closely to the design of Microsoft’s VisualBasic: rapid-prototyping applications which focus on the drag-and-drop construction of forms and windows out of a collection of standard user interface widgets. Interaction is wired up via event handlers, but the underlying programming model is strictly imperative. Data lives in mutable variables. Applications are built by developers and shipped sealed and inviolate to mere users.

I see HyperCard differently. It certainly had event-based programming wired up to interactive buttons and fields, but there was something evasively softer and more pliable about it as a medium. It broke down the hard distinctions we tend to take for granted between programs and documents, developers and users. When I designed Decker, I wanted to build something that retained the intuitive and powerful stack of cards metaphor as well as HyperCard’s emphasis on being a painting tool.

HyperCard and Decker organize the world like a stack of paper index cards. One card is visible at a time. The user moves from card to card in an imaginary space, much as a web browser navigates between webpages. By default, cards are laid out in a linear sequence:

As in HyperCard, Decker allows a user to cycle through cards in this sequence with cursor keys1. If you’re creating something like a flipbook or a presentation, this may be the only navigation structure needed!

Cards have a fixed size, large enough to display an idea- a few images, a few sentences and buttons- but small enough to motivate breaking large ideas down. An entire novel wouldn’t go on a card; perhaps a card is a chapter, a page, or a single paragraph annotated with supporting material. By breaking ideas into discrete cards, they become easy to rearrange and cross-reference.

Viewed within the broader sweep of Bill Atkinson’s body of work, I see HyperCard first and foremost as a better, more refined version of MacPaint. The user interface bristles with features related to pushing around pixels on cards:

Most VisualBasic-like tools permit programmers to import graphics and display them upon forms somehow, but they rarely feature any kind of built-in image editing functionality. Placing drawing tools directly at a user’s disposal at all times may seem like a subtle difference, but it profoundly changes the workflow. In HyperCard or Decker, if I want a button with a custom icon I can simply use the pencil tool to draw on a card background and position a transparent button on top:

If I want to highlight and annotate some text in a field, I can likewise make it transparent and doodle away:

Custom brushes allow for a broad range of painterly stipples and directional textures. With a customized color palette, the results can be suprisingly delicate:

Don’t underestimate the value of your sketchbook being your development environment!

A user can impose non-linear navigation between cards with links, buttons, or other scripted contrivances. Cards thus represent the nodes of a graph, or the states within a state machine.

Many applications and games can be modeled by state machines. An adaptation of a Choose Your Own Adventure story doesn’t need any programming, just cards and a web of connections for a player to explore.

Cross-referenced cards don’t have any intrinsic physical relationship with one another, but using transitional visual effects can suggest these relationships and help to anchor the user:

Moving between cards is assisted by a built-in history mechanism: many paths can lead to a card, so it is useful to be able to return whence you’ve come:

In Lil, the scripting language of Decker,

go[SomeCard]

sleep[30]

go["Back"]

Having this mechanism makes cards an adequate substitute for modal dialogs2.

Decker embraces reified state: persistent information lives within widgets that reside upon cards. Code and data have a “physical” location within the deck. If we have several cards with consistently-named widgets, we can think of each card as a record within a database.

Valentiner, a greeting-card application built in Decker, uses “record cards” to store background images and clip-art characters for card covers (alongside punny oneliners):

To populate a listbox with the names of all the clipart, the cards of a deck are queried based on a naming convention:

extract "char_%s" parse key where key like "char_*" from deck.cards

These records are schemaless and freely extensible: they could contain additional notes or extra drafts of art in an ad-hoc fashion. We can easily add or remove record cards without needing to touch any code.

Like HyperCard, Decker is built around message-passing. Interacting with widgets on a card produces messages which are handled by scripts on the widgets, “bubbled up” to the enclosing card’s scripts, or even handled by scripts attached to the deck itself. Scripts can also send their own “synthetic” event-messages to distant parts of the deck.

Let’s say we’re using a card to keep track of important information:

We could send messages that simulate clicking the buttons of our form from elsewhere in the deck:

safetyCounter.widgets.button1.event.click

But we could provide a cleaner interface by moving all the logic to the card script,

on increment do days.data:days.data+1 end

on reset do days.data:0 end

Allowing external scripts to send messages to the same event handlers as the buttons:

safetyCounter.event.reset

If we then added features,

It would only be necessary to update internal logic; external scripts can stay the same:

on increment do days.data:days.data+1 end

on reset do

days.data:0

screwups.data:screwups.data+1

play["oh no"]

end

By providing an encapsulated container for state and code, and exposing a message-passing interface to the outside world, cards can function like a Smalltalk “Object” combined with a graphical user interface; equally accessible to humans or scripts.

By sprinkling interactive elements onto a card, we can build tiny ad-hoc tools that support the task at hand.

Say, a button that mirrors the card background we’re sketching to help make mistakes more apparent:

on click do

card.image.transform.horiz

end

A button that saves a screenshot of a specific region of a card, masking transparency into opaque white:

on click do

write[app.render[card].map[0 dict 32].copy[me.pos me.size]]

end

A live editor for the 1-bit patterns in our drawing:

Or perhaps an interactive preview of animations:

Building exactly the tool we need, operating on data immediately at hand, is often tremendously simpler than making something general-purpose and reusable. Saving and restoring, drawing tools, clipboard operations, text editing, and even undo history are already provided by the substrate.

Since these tiny tools live on cards, they naturally travel with the rest of a project. Hidden “backstage” cards are a great way to illuminate the inner workings of your projects to future tinkerers!

As we’ve seen, HyperCard’s “stack of cards” metaphor can scale usefully to projects along a wide range of complexity, from collections of mostly static data to involved program-like constructions. Understanding the benefits of this model has valuable applications for the construction of malleable, modular systems.

This behavior can be overridden for specific cards or the entire deck by defining a custom event handler for navigate[dir]. ↩︎

As a convenience, Decker has primitive alert[] modals, and more elaborate systems can be furnished with modules. ↩︎